I’ve always wanted to invent my own brand of soda called Peepsi! However, I’m positive I’d get a cease and desist letter for trade name infringement from Pepsi before I could screw the cap on my first bottle. Although there is a difference between Peepsi and Pepsi, the consumer confusion would likely turn into a winnable trade name infringement case. Generally, infringing on a business’s trade name comes at the expense of a company’s good will it has established over time, in Pepsi’s case, over a century. So let us discuss consumer confusion and trade name infringement.

Consumer Confusion and Trade Name Infringement

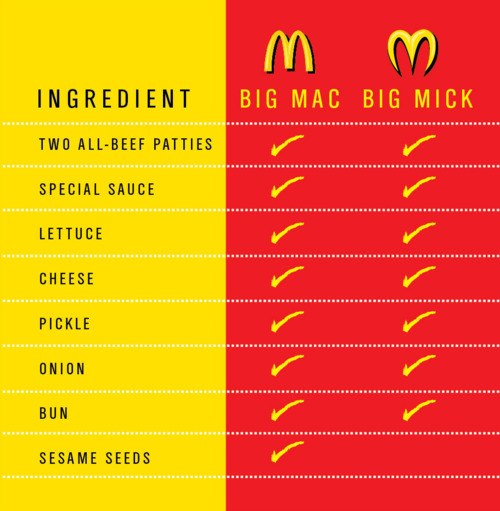

In the famous movie “Coming to America” starring Eddie Murphy, John Amos played the role of Cleo McDowell, an entrepreneur who owned McDowell restaurants which eerily resembles McDonalds. In the film, he’s quoted as saying “… me and the McDonald’s people got this little misunderstanding. See, they’re McDonald’s… I’m McDowell’s. They got the Golden Arches, mine is the Golden Arcs. They got the Big Mac, I got the Big Mick. We both got two all-beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles and onions, but their buns have sesame seeds. My buns have no seeds.” Great fodder for film but in real life this would hardly fly. Specifically, under 15 U.S.C §§ 1051 et seq., also known as the Lanham Act that governs consumer confusion cases, a specific set of guidelines “protects the owner of a federally registered mark against the use of similar marks if such use is likely to result in consumer confusion, or if the dilution of a famous mark is likely to occur.”[1]

Establishing Trade Name Infringement

Typically, in determining whether consumers were unjustly confused to the detriment of an established registered mark, a court will consider seven factors. In consideration of these seven factors, the court uses a balancing test in deciding whether consumer confusion has occurred. The seven major factors a court will use in determining the “likelihood of confusion,”, include (1) the similarity of the plaintiff’s and defendant’s goods or services, (2) the identity of retail outlets or purchasers, (3) the identity of advertising media, (4) the “strength” (for example, inherent distinctiveness) of the trade name, (5) the defendant’s intent, (6) the similarity of the trade names, and (7) the degree of care likely to be used by consumers. [2]

So in our hypothetical case involving Cleo’s McDowell restaurant, first a court will consider the fact that both McDonalds and McDowell’s are in the fast food industry, primarily selling hamburgers, specifically “two all-beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles and onions.” Being that both entities are selling virtually identical products (minus the seeds), element one will likely go into McDonalds favor.

Second, the court would look at the fact that both restaurants use fast-food outlets to target and serve its customers. If Cleo were operating out of, let’s say a food truck instead of an actual fast-food restaurant, a court might give deference to that fact. However, here, both entities are using similar outlets which would likely serve as another blow to Cleo’s consumer confusion defense.

Third, with regards to identity of the advertising media, presumably McDowell’s advertised primarily through community presence and its logo. As Cleo put it, “McDonalds has the gold arches, while his logo uses the golden arcs.” Here, the logo’s and even the typeface are extremely similar. This form of self-advertising media bears a striking resemblance in both restaurants which would likely land another check in McDonald’s favor.

Fourth, the court would determine the strength of the plaintiff’s own brand. Here, McDonald’s – having been in existence since the 1950’s – would have amassed a significant amount of good will under its brand by now. Though it is unknown how long Cleo McDowell’s franchise has been in existence, it unlikely pre-dates McDonalds.

Fifth, it is unclear that Cleo McDowell’s intent was to purposefully confuse consumers; however a court can and will infer intent by conduct. Specifically, the closeness of the brand, the logo, the type of food sold, the similarity in uniforms and the fact that when Cleo is first confronted by King Jaffe Joffer, he is seen reading a McDonald’s Operation Manual. [3]

Sixth, with regards to the similarity in trade names, a court will take into consideration the use of one’s family name in contrast to an existing trade name. However, courts have held that “the right of an individual to use his or her own name in connection with a business must yield to the need to eliminate confusion in the marketplace.” B.H. Bunn Co. v. AAA Replacement Parts Co., 451 F.2d 1254, 1266 (5th Cir. 1971) (“[O]ne may be forbidden to use even one’s own name, absent other distinctions, if the total effect of using it is to create confusion as to source.”) [4] Here, while Cleo used his family name, unfortunately there simply aren’t enough distinctions between the McDowell’s and McDonald’s brand to distinguish the similarities.

Lastly, in establishing the degree of care likely to be used by consumers, all McDonald’s would need to establish is a “likelihood of confusion” arising from the defendant’s use of the same or similar name.” WSM, Inc. v. Hilton, 724 F.2d 1320, 1325 (8th Cir. 1984). [5] This could be satisfied constructively or literally. For instance, if a customer, on any occasion, entered McDowell’s thinking it was McDonald’s, or attempted to use a McDonald’s coupon, or even referred to Cleo’s “Big Mic” as a “Big Mac” when placing an order, it would likely satisfy the last element. [6]

Conclusion

In conclusion, given the totality of the circumstance resulting from the balancing test, a court would likely determine that Cleo’s restaurant is liable for customer confusion and trade name infringement. So remember that while you’d like your product to be recognized by the masses for what it is, there could be serious confusion for what it isn’t. My personal brand of soda, Peepsi, while specific and individual to me, is unlikely to be easily differentiated by a consumer. This causes consumer confusion and ultimately infringes on Pepsi’s established good will. So if you’re contemplating starting the next big burger franchise called Burger Queen, think again about how consumer confusion and trade name infringement.

[1]LANHAM ACT | WEX LEGAL DICTIONARY / ENCYCLOPEDIA | LII / LEGAL INFORMATION INSTITUTE, http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/lanham_act (last visited Oct 23, 2014)

[2]REMEDIES FOR TRADE NAME INFRINGEMENT, http://www.fwlaw.com/news/189-remedies-trade-name-infringement (last visited Oct 23, 2014)

[3]COMING TO AMERICA – WIKIPEDIA, THE FREE ENCYCLOPEDIA, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coming_to_America#McDowell.27s (last visited Oct 23, 2014)

[4]REMEDIES FOR TRADE NAME INFRINGEMENT, http://www.fwlaw.com/news/189-remedies-trade-name-infringement (last visited Oct 23, 2014) See Basile S.P.A. v. Basile, 899 F.2d 35, 39 (D.C.Cir. 1990) (limiting right of watch manufacturer to use family name “Basile,” where prior user had obtained trademark over use of the name); Perini Corp. v. Perini Construction, Inc., 915 F.2d 121, 124 (4th Cir. 1990) (limiting second comer’s right to use family name “Perini,” where name had acquired secondary meaning in the construction industry through prior use); B.H. Bunn Co. v. AAA Replacement Parts Co., 451 F.2d 1254, 1266 (5th Cir. 1971) (“[O]ne may be forbidden to use even one’s own name, absent other distinctions, if the total effect of using it is to create confusion as to source.”)

[5]REMEDIES FOR TRADE NAME INFRINGEMENT, http://www.fwlaw.com/news/189-remedies-trade-name-infringement (last visited Oct 23, 2014)

[6]Id.